April 23, 2000

Rapping in Whiteface (for Laughs)

ForumJoin a Discussion on Popular Music

By JODY ROSEN

C Paul Barman, a 25-year-old Brown University graduate from Ridgewood, N.J., is pioneering a new hip-hop persona: the rapper as schlemiel. On Mr. Barman's debut EP, "It's Very Stimulating," we meet a character unlike the heavies, braggarts and smooth lotharios who normally narrate rap songs -- a white, Jewish, Woody Allenesque neurotic who is nerdy, girl crazy and sexually hapless. "My sex life is pathetic," Mr. Barman announces at the record's outset. "That's why I fantasize in four out of five songs." The first of those songs, "The Joy of Your World," sets the tone. It is a catalog of self-deprecating "boasts" and romantic misadventures: "I'm pond scum," he raps. "If you want sex with me/ Be prepared for bad sex/ And slapstick."

C Paul Barman, a 25-year-old Brown University graduate from Ridgewood, N.J., is pioneering a new hip-hop persona: the rapper as schlemiel. On Mr. Barman's debut EP, "It's Very Stimulating," we meet a character unlike the heavies, braggarts and smooth lotharios who normally narrate rap songs -- a white, Jewish, Woody Allenesque neurotic who is nerdy, girl crazy and sexually hapless. "My sex life is pathetic," Mr. Barman announces at the record's outset. "That's why I fantasize in four out of five songs." The first of those songs, "The Joy of Your World," sets the tone. It is a catalog of self-deprecating "boasts" and romantic misadventures: "I'm pond scum," he raps. "If you want sex with me/ Be prepared for bad sex/ And slapstick."

|

Photographs by Rahav Segev, Photographs by Rahav Segev,

The Associated Press (center)

|

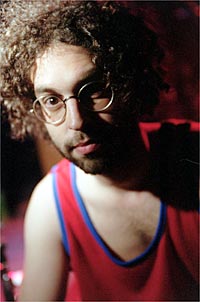

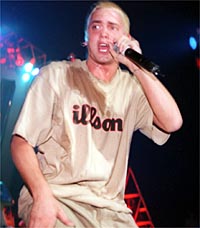

White rappers like MC Paul Barman, top, Kid Rock, center, and Eminem, bottom, seem determined to build on the outlandishness of rap jesters like Biz Markie and Ol' Dirty Bastard. Their comic postures range from the frequently brilliant to the endearingly dumb to the monumentally witless.

|

Mr. Barman's taste for outrageous self-deflation isn't the only thing that makes "It's Very Stimulating" a surreal departure from the rap norm. Shunning hip-hop slang and diction, Mr. Barman raps in a nerd's manic, high-pitched voice and packs his songs with strange similes, bookish arcana and highbrow allusions. He name-drops the artist Chuck Close and the Polish filmmaker Krzysztof Kieslowski; he likens a sex act to the algebraic diagrams of the 19th-century British logician John Venn; he invokes the Ragnarok, Scandinavian mythology's version of the Apocalypse.

One song is set in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where an assignation takes place "over the Grace Rainey Rogers room rostrum." Like any worthwhile rapper, Mr. Barman knows how to sling a good insult, but his grievances are emphatically post-collegiate and upper-middle class. In "School Anthem," a song about education reform, he decries his high school's "test-based curriculum" and disses Choate, the elite Connecticut prep school. MC Paul Barman's worst enemies? Frat boys: "Smirkin' jocks with hackysacks/ In Birkenstocks and khaki slacks."

"It's Very Stimulating" is, deliberately, the whitest hip-hop record ever made. It wants to be one of the funniest: Mr. Barman is keen to wring as much humor as possible out of the dissonance between his very "white" concerns and the medium in which he has chosen to amplify them. His style of rhyming is itself a parody of geeky fastidiousness. In contrast to most rappers, who are willing to depart from strict rhyme schemes in pursuit of the deeper beauties of funk and flow, Mr. Barman strives to rhyme nearly every syllable he speaks. The result is a rigid but comically singular style, bursting with intricate rhymes -- "suck toes," "fructose," "Chuck Close" -- that sound like poetry scrawled by a bored graduate student to avoid nodding off in a seminar. Mr. Barman's comedic cause is buoyed by the presence of Prince Paul, the producer responsible for some of the most whimsical records in the hip-hop canon. The sound he has created for "It's Very Stimulating," a buoyant mix of samples from children's records, xylophone trills, snippets of in-studio horsing around and Bing Crosby singing "Blue Tail Fly," recalls his work on De La Soul's 1989 album "Three Feet High and Rising," and it bathes Mr. Barman's wacky songs in a fittingly garish Day-Glo light.

In commercial terms, MC Paul Barman is a curio: this 18-minute-long record on the independent label Wordsound is not about to make him a household name. But he is emblematic of a trend that has penetrated the rap music mainstream: the increasing prominence of white rappers who fashion themselves as rhyming comedians. Today's biggest white rap acts -- the Beastie Boys, Eminem, Kid Rock, Insane Clown Posse -- make comedy the cornerstone of their identities and have shown a determination to up the ante on the outlandishness of rap jesters like Biz Markie and Ol' Dirty Bastard. These comic postures range from frequently brilliant (Beastie Boys, Eminem) to endearingly dumb (Kid Rock) to monumentally witless (Insane Clown Posse), but what is notable is the apparent consensus among white rappers about their need to play hip-hop for laughs.

It is a phenomenon rooted in hip-hop's preoccupation with authenticity and "keeping it real." At its core, rap authenticity is based on a commitment to giving musical and poetic expression to urban African-American experience, to reflecting the changing slang, styles and values of black youth.

White rappers have naturally had a difficult time finding a voice in the music Public Enemy's Chuck D likened to a black version of CNN. When groups like 3rd Bass and House of Pain tried to project the street-smart machismo associated with hardcore rap, the results were strained and insipid. The infamous Vanilla Ice brought hip-hop to an all-time low with his flimsy rhymes, imaginary criminal record and preposterous pants.

In the post-Vanilla Ice era, white rappers' most potent strategy has been defensive: to avoid being the butt of others' jokes, they have embraced irony, accentuating the artifice of, and maintaining a winking distance from, their rap personas. You see it in the bug-eyed, cartoon violence of Eminem's vivid narratives, in Kid Rock's cavorting with a midget sidekick, in Insane Clown Posse's horror movie face paint, in the Beastie Boys' campy music videos: for white rappers, keeping it real usually means keeping it fake.

he discomfort of white rappers about their place in hip-hop stands in marked contrast to the cavalier attitude of an earlier generation of white musicians toward black music. To greater and lesser degrees, Elvis Presley, the Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin and other major artists of the rock era made careers out of savvy appropriations of blues and R&B. At its crudest, this practice could feel like outright theft and verge on a kind of latter-day blackface minstrelsy. It is doubtless a sign of social progress that white rappers feel conflicted about the propriety of cultural piracy.

he discomfort of white rappers about their place in hip-hop stands in marked contrast to the cavalier attitude of an earlier generation of white musicians toward black music. To greater and lesser degrees, Elvis Presley, the Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin and other major artists of the rock era made careers out of savvy appropriations of blues and R&B. At its crudest, this practice could feel like outright theft and verge on a kind of latter-day blackface minstrelsy. It is doubtless a sign of social progress that white rappers feel conflicted about the propriety of cultural piracy.

But what white rappers have gained in raised consciousness may have boxed them in artistically, limiting them to self-satirizing comedy routines, the subtext of whose every joke mocks the absurdity of white guys trying to play a black man's game. The notion of a white rapper is no more inherently foolish than that of a bunch of middle-class Englishmen singing the blues. Yet the Rolling Stones were jokers not afraid to take themselves seriously, and that unself-conscious ambition propelled them above the awkwardness of their appropriations, freed them to speak unironically and to claim an exalted place in the tradition they first entered as interlopers.

Among white rappers, only the Beastie Boys and Eminem have summoned that same fearlessness, and it has elevated their rap-comedy above irony into something that arcs toward pathos. Though the Beastie Boys ground their rap in the basics of old school hip-hop -- boasts, gibes, party chants -- they are musical adventurers who have been instrumental in expanding hip-hop's sonic palette. Their dedication to musical eccentricity mirrors a broader commitment to the virtues of weirdness: the Beastie Boys' records are diaries of their pop culture obsessions, and when they rap about their skill at the board game Boggle or romp around in ridiculous costumes, they are not so much sending themselves up as inviting everyone to join them in a state of happy-go-lucky tomfoolery.

hirteen years ago, the Beastie Boys burst onto the pop charts with the party anthem "Fight for Your Right," and while they have disavowed the song's bratty trappings, they have never abandoned its spirit: their rap continues to champion goofiness as a cause for pan-racial celebration.

hirteen years ago, the Beastie Boys burst onto the pop charts with the party anthem "Fight for Your Right," and while they have disavowed the song's bratty trappings, they have never abandoned its spirit: their rap continues to champion goofiness as a cause for pan-racial celebration.

Eminem, one of the most poetically dexterous rappers, uses comedy to probe darker places. He is a master of gallows and gross-out humor, whose narratives about drug overdoses, murder and masochism are launching pads for a fusillade of one-liners. But Eminem's lyrics offer more than gratuitous shock value: he is hip-hop's first white bluesman, whose grimly funny songs, filled with violence and self-loathing, movingly describe the hardships of a white underclass life. Even more ingeniously, Eminem conflates his death-haunted alienation and his embattled status as a white rapper to produce a kind of existentialist comedy. "Some people only see that I'm white, ignoring skill," he raps. "How . . . can I be white? I don't even exist." Elsewhere, he declares: "I'm not a real person. I'm a ghost trapped in a beat."

MC Paul Barman has no pretensions to that kind of tragicomic grandeur; he just wants to write clever rhymes and clown around. Hip-hop prizes originality, and on that count Mr. Barman is a success. He has cornered the market on over-educated, smarty-pants rap; no one will ever again rhyme "booty" with "Susan Faludi" without being accused of ripping off Mr. Barman. But there is a difference between a funny rap record that is built to last and a novelty record; one cannot escape the feeling that "It's Very Stimulating" is the latter. Seemingly the only things separating Mr. Barman's raps from the annoying pop music parodies of Weird Al Yankovic are Prince Paul's sturdy beats and the occasional Wallace Shawn reference. Overall, there is a wearisome sameness to "It's Very Stimulating." Behind every one of Mr. Barman's japes -- from his corny shout-outs to "towns, hamlets and neighboring islands" to his off-key singing of a chorus based on Lauryn Hill's "To Zion" -- looms the same big punchline: Isn't it funny how white I am?

Overcoming that kind of reflexive insecurity, without blundering into minstrelsy, is the challenge that continues to face white rappers, even as they increasingly view hip-hop as a music to which they can stake some claim. "Your talents are bite-size," MC Paul Barman taunts his fellow rapper Princess Superstar on the duet that concludes his EP. "It's no surprise you rhyme with white guys." But the joke is out of date. The next few years are sure to produce the biggest wave yet of white rappers; undoubtedly, many of them will be as talented as their black peers. But will they be comfortable in their own skin?

Jody Rosen, a freelance writer in New York, specializes in pop music.